Homicide detective’s book describes ‘How the Police Generate False Confessions’

- Tom Jackman

- Jun 2, 2017

- 6 min read

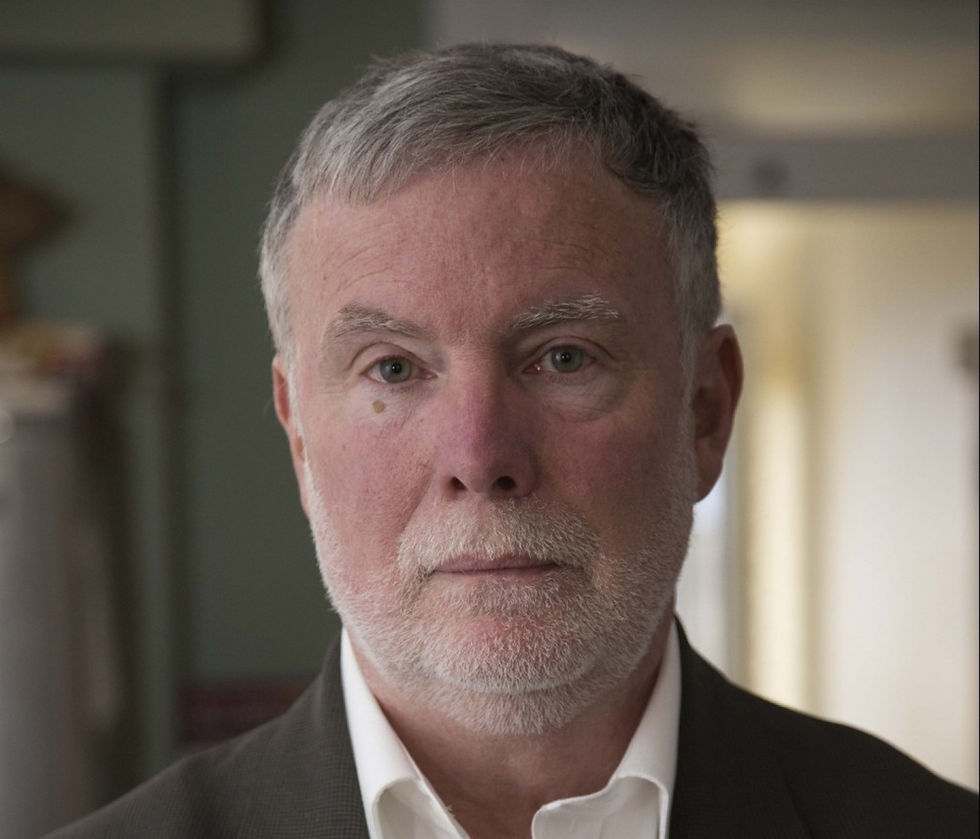

James L. Trainum, retired Washington, D.C., homicide detective and author of the book “How the Police Generate False Confessions. (matte design)

“If you plan on being arrested for a felony, you must read this book.”

— Tom Jackman, The Washington Post

Also, if you have an interest in fairness, justice and preventing wrongful convictions, then the new book “How the Police Generate False Confessions,” by former Washington, D.C., homicide detective James Trainum is an important read. It takes you inside the interrogation room to see how investigators extract admissions from innocent people, and how the justice system can fix this persistent problem, seen in high profile cases such as the Central Park Five, the Norfolk Four and the teenaged suspect from Wisconsin in the Netflix series “Making a Murderer.”

It’s a phenomenon that remains, understandably, incomprehensible to many. Someone “admits” to a crime they did not actually commit, to a police detective of all people, knowing they face a long prison sentence for doing so. Who would do such a thing? In all three of the cases above, young men admitted to committing rape, and in two of them to gruesome murders.

Trainum, 61, spent 17 years in homicide for the Metropolitan Police Department, retiring in 2010. He was the lead detective on the high-profile Starbucks triple murder in Georgetown in 1997, which he eventually helped solve in 1999. But in 1994, Trainum had an eye-opening experience when he obtained his own false confession. After a 16-hour interrogation, a woman told him she and two men had killed a man whose body was found, bound and beaten, near the Anacostia River. She was charged with first-degree murder. But she recanted weeks later, and Trainum found proof that she couldn’t have been where she originally claimed at the time of the slaying. The charges were dismissed.

“What did I do,” Trainum asked himself, “to convince this person to tell me something she didn’t do? How did she get all those details she shouldn’t have known?” He realized that implying that her cooperation would get her better treatment from the prosecutors, and minimizing her role in the case to obtain her testimony against co-defendants, as well as a mistaken handwriting analysis and a bogus “voice stress test,” got her to confess.

Trainum began researching the concept of false confessions, not widely discussed in the 1990s. At that time, five New York teenagers were in prison for allegedly raping a woman in Central Park in 1989. Though DNA later proved an unrelated man had committed the crime, some people still believe the Central Park Five are guilty, including presidential candidate Donald Trump. “It just shows you what the power of a confession is,” Trainum said. “In spite of the overwhelming evidence, physical and otherwise, people still believe a confession trumps everything. No pun intended.”

False confessions are now understood to be a significant contribution to wrongful convictions. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, of 1,900 wrongful convictions in their data base, 234 were caused by false confessions, or about 12 percent.

Trainum said detectives are just following their training, which is often minimal, and which allows for not only unethical tactics but lying by investigators, who can falsely tell a suspect they failed a polygraph, that other people identified him as a suspect and that evidence indicates he committed the crime. Trainum summarizes the approach that most detectives take to a suspect in “the box”:

1. Conclude that the suspect is guilty

2. Tell them that there is no doubt of their guilt

3. Block any attempt by the suspect to deny the accusation

4. Suggest psychological or moral justifications for what they did

5. Lie about the strength of the evidence that points to the suspect’s guilt

6. Offer only two explanations for why he committed the crime. Both are admissions, but one is definitely less savory than the other

7. Get them to agree with you that they did it

8. Have them provide details about the crime

Now Trainum repeatedly acknowledges that police often elicit confessions from actually guilty people, sometimes after long or difficult sessions. But he said everyone in the system — detectives, defense attorneys, prosecutors and judges — must be aware of the possibility of false confessions, and be certain to do the legwork which corroborates or disproves such statements.

In 1995, Washington, D.C., homicide detective Jim Trainum was shown using the latest technology, and a new crime data base, to solve cases. (Robert Reeder/The Washington Post)

Trainum writes that suspects often make false confessions because they make a bad cost-benefit analysis. They think that confessing will allow them to go home, or allow them to face lesser charges, or protect other people. In “Making a Murderer,” 16-year-old Brendan Dassey confesses to murder and then asks if he can return to class at his high school. That confession and others were later used against him at trial and he was convicted, though in August of this year the case was overturned after a federal judge ruled the confessions were coerced and involuntary. “Thank God for videotape,” Trainum said of the confession. “Those detectives were not seeking the truth. They’re seeking a confession.”

But Dassey’s multiple confessions, including one in which the detectives tell him how the victim was killed after he repeatedly provides the wrong causes, had held up through trial and appeals court rulings for years. “One of the biggest problems,” Trainum said, “is the judges don’t worry about reliability [of a confession]. They say it’s up to the jury to decide that. They only worry about if it is admissible. There’s kind of a movement to shift the reliability back to the judges.” He noted that judges will hold hearings on the reliability of eyewitnesses or the reliability of jailhouse informants. “They don’t do that with confession evidence. And they really should. Once a confession gets in front of a jury, the defense attorney has an uphill battle. The jurors think, ‘I would never confess to something I didn’t do.'”

The National Registry of Exonerations shows that 15 percent of wrongful convictions occurred with guilty pleas. That was the case with Danial Williams and Joseph Dick, two sailors in the Norfolk Four who falsely confessed and pleaded guilty in the rape and murder of a woman in Norfolk in 1997. Another man’s DNA later linked him to the crime and he said he committed it alone. Williams’ and Dick’s sentences were commuted but not fully pardoned by then-Gov. Tim Kaine (now a vice presidential candidate) in 2009, and in an appeal to have their convictions vacated, U.S. District Court Judge John A. Gibney Jr. ruled last month that, “By any measure, the evidence shows the defendants’ innocence…Stated more simply, no sane human being could find them guilty.”

So what to do about false confessions? Trainum has many suggestions, starting with police videotaping all interrogations. Many departments still don’t do it. “Law enforcement doesn’t want you in that interrogation room,” Trainum said. “They don’t want you to see what they’re doing, because some of the stuff they know is not appropriate.”

But the ex-detective also advocates adopting the British method of investigation, in which the questioning is not adversarial and is instead focused on eliciting the truth, as opposed to only a confession. It is known as P.E.A.C.E., for preparation, engagement, accounting, closure and evaluation. It was imposed on British police after a spate of false confessions, and Trainum said it can be used just as effectively as the current American method.

The P.E.A.C.E. model is only starting to make inroads in the U.S., and it would require extensive training and money. He thinks the skill of interviewing is undervalued. “People think talking to people is a natural thing,” Trainum said. “It’s not. That’s why psychiatrists undergo so many years of training. You have to be able to build a rapport without threats or promises. Cops make the worst private investigators. We have too many bad habits.”

Trainum, now a consultant for the Innocence Project, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children and various defense lawyers, has not exactly been embraced by his former colleagues, who began calling him “Benedict Trainum” when he was still on the force. He said he is shunned by some older cops, but younger ones are more open to his ideas.

“I hope law enforcement reads my book,” Trainum said. “With my consulting business, I want to be put out of business. I would rather they make good cases that I can’t touch.”

I asked Brandon Garrett, a University of Virginia law professor who has focused on wrongful convictions, about Trainum’s book. “It is such an important new book,” Garrett said. “For decades, we have seen false confession after false confession lead to tragic wrongful convictions of the innocent while serious criminals go undetected. The courts have done little to respond to abuses in the interrogation room; if anything they have eroded constitutional protections, such as the right to remain silent. Trainum explains that for police, there is another way. Overly coercive interrogation techniques not only produce false confessions but they are not good at uncovering good information. In the U.K. and in more agencies in the U.S., police have changed gears, turning from psychologically coercive techniques to information gathering techniques. Trainum and his book are at the forefront of a revolution in police interrogations.”

Source: Tom Jackman has been covering criminal justice for The Post since 1998, and now anchors the new "True Crime" blog. Follow @TomJackmanWP

Comments